| This post is a revised (and translated) version of the aricle originally written on the request of the Hungarian Jewish Cultural Association. |

Of course, at that time the history of the Jews in Mallorca already looked back on a long time. Our sources report about a large Jewish community moving to the island in the 1st century, after the destruction of Jerusalem, and in the 5th century a member of this community was the imperial administrator of the whole Mallorca. The community also flourished after the Arab conquest, and their quarter was right next to the Caliph’s palace, on the place of the later Dominican church.

When James I, King of Aragonia and his wife, Violant of Hungary on 31 December 1229 entered Medina Mayurqa, occupied from the Arabs, their first provisions included the distribution of lands to the Catalan Jews financially supporting the conquest, and houses in today’s St. Bartholomew Street for the Jewish soldiers who personally participated in it as a special company. For a century the king and his successors largely based the financial and economic management of the island on the Jews of Palma, and provided them with various privileges. This period was the golden age of the Jews in Mallorca. The growth of their population and influence is indicated by the foundation and extension of the Call, the Jewish neighborhood at the southeastern part of the old town, around the modern Sol and Montesión Streets, with three large and beautiful synagogues: on the site of one of them the Jesuit church stands today, while the place of the other two is only approximately known. Here, in the Call lived and worked the two great geographers and cartographers of the Catalan world, Abraham and Jafudà Cresques, father and son. The latter is today remembered by a statue in front of their former house, opposite the former fortress of the Knights Templar, which in the Arab times was commonly referred to as “the fortress of the Jews”.

The Jewish community preserved its self-organization and its members their social status and wealth even after the conversion in 1391. Now as a Christian confraternity they provided for the maintenance and upbringing of the poorer members of the community According to contemporary reports, many of them continued to live at home according to Jewish custom, and they married only among themselves. The Catholic church throughout all the 15th century tried with great force to end their secret Judaism, and in this effort the Spanish Inquisition, which appeared in 1488 on the island, was a powerful weapon. Until 1545, the last examination for secret Judaism, 537 converted Jews were condemned to death, of whom 82 were actually burnt at the stake, wile the majority managed to escape in time from the island. Then one and half century of relative peace followed, but in the early 1670s the anger of the inquisition flared up once more. In the next years several proceedings were taken against hundreds of secret Jews, and during the infamous Cremadissa, the “mass burning” in 1691 several “relapsed” Jews were burned alive in today’s Plaza Gomila, which after then was called for a long while el fogó dels Jueus, “the stake of the Jews”.

Besides the abuses of the inquisition, the xuetas – according to popular etymology, this word comes from Catalan xuía or xulla, meaning “bacon” or, in an extended sense, “pork”, but most probably it comes from the Catalan juetó, “little Jew” – suffered also a number of other discriminations. The neteja de sang, the “purity of blood” was a necessary condition of the admission to most religious and secular organizations – such as urban guilds and the army –, so the descendants of former Jews and Moors had non place there, neither the “pure blood” families gave them their daughters. Many propaganda pamphlets were published against them, which openly questioned the sincerity of their Christian faith and demanded their segregation. Finally in 1773 the xuetas addressed a petition to the court, asking for their emancipation, which, even after many decades of debates, achieved no results.

The distinction of the xuetas – and thus their isolated community – has survived until the end of the 20th century. Their legal discrimination, however, was cancelled during the century, but the inhabitants of Palma still know well in which houses live and which shops sell xuetas: the latter mainly in the Street of the Silversmith, where on most jewelry stores you can still read the “fifteen names” of the fifteen largest xueta families. According to a 2001 poll, 30% of “pure blood” Mallorcans would never marry a xueta, and my xueta friend told that he was made aware of his xueta origins when in the first class he was mocked with this by the other children, and when his devout Catholic parents then told him about their origins.

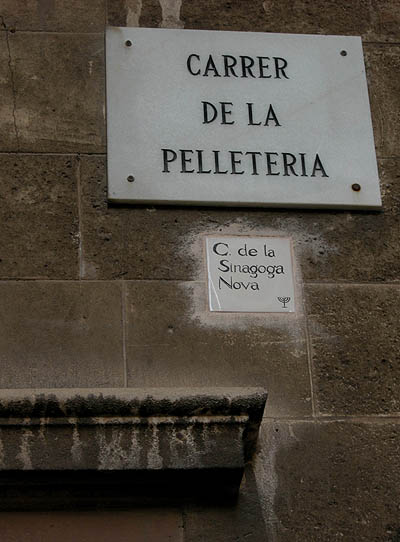

Besides, a “xueta Renaissance” also can be experienced since the 1960s. The xuetas, the other inhabitants of the island and the Jews of all the world turn with increasing interest to the Jewish past of the island. An abundant and important historical literature is emerging around them, and they also created a number of important cultural associations, like the ARCA-Llegat Jueu (Jewish Heritage), the Memòria del Carrer researching the history of the island, and they also have a journal of their own called Segell, the name of the first Jewish street of the city. And in the former Jewish quater, along with the Catalan names, now also appear street signs with the ancient Jewish names of the streets.

We will report on this in detail and in several posts in the following weeks.

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario