The Italian soldier who is on guard against nothing and commenting on himself in the caption is Carlo Manfrini, nineteen years old at that time. Manfrini’s Russian photos have been kept for many years in his home in Dozza near Bologna, at a thousand and five hundred kilometers away from the locations photographed between June and November 1942.

Unlike lots of other photos he mainly took as a research agronomist on plants, leaves and flowers affected by diseases and insects, those included in the little book Diario di Russia, 13 giugno – 12 novembre 1942, before being published in 2010 by Guaraldi Publisher never made part of the family albums his children used to leaf through with interest and care after the war. These photos of small 6×6 format have been kept for years in a separate box which was opened for the children’s curiosity only in the presence of the photographer who commented in a reassuring and ironic tone on the stories behind the photos.

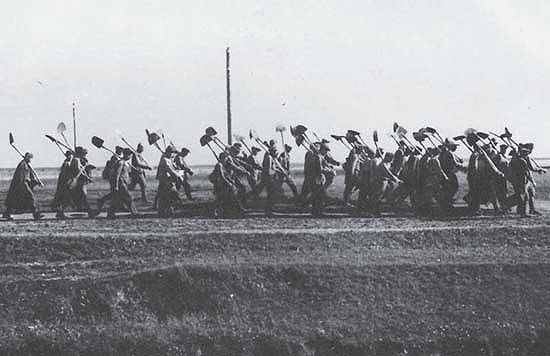

Manfrini left Padua on June 13, 1942 as a member of the Sforza Division which had to join up the Eighth Army in defense of the Don front. The division was transported in goods and cattle wagons where the soldiers soon started to be affected by dysentery. They traveled through Austria and Slovakia to Lviv, from where they went on by road towards Kantemirovka.

Station of Lviv. Trucks unloaded and aligned in the square near the ghetto. Most of them are Fiat 504 trucks carrying anti-aircraft guns on the trailer. I remember that the leftover of the food, thrown under the cars, attracted the kids from the ghetto. They ate everything, even browsing for pieces among the oil leaking from the vehicles. The more mature girls prostituted themselves for a loaf of bread.

Station of Lviv. Trucks unloaded and aligned in the square near the ghetto. Most of them are Fiat 504 trucks carrying anti-aircraft guns on the trailer. I remember that the leftover of the food, thrown under the cars, attracted the kids from the ghetto. They ate everything, even browsing for pieces among the oil leaking from the vehicles. The more mature girls prostituted themselves for a loaf of bread. A short stop during the journey. The trucks are camouflaged with green branches. In the foreground a soldier, an artillery corporal wearing working uniform with leather bootlegs and boots.

A short stop during the journey. The trucks are camouflaged with green branches. In the foreground a soldier, an artillery corporal wearing working uniform with leather bootlegs and boots.In order to deliver the dispatches and to maintain the communication between the beginning and the end of the convoy, Manfrini moved about on a single-cylinder motorbike Sertum 500 VL. One day he was so exhausted that he fell off the motorbike and was barely spared by the truck behind him. The truck could stop, but not without running into the truck passing in front of it, and the cannon pulled by it broke its windscreen. “From the day” – he wrote – “I was assigned to the truck of the bataillon’s office”.

By passing through an Ukrainian village, we come across a column of Russian prisoners brought back from the front. To the left you can see the truck with the broken windscreen after the motorbike accident.

By passing through an Ukrainian village, we come across a column of Russian prisoners brought back from the front. To the left you can see the truck with the broken windscreen after the motorbike accident.Many photos show the life of the soldiers and of the peasants behind the front line in the summer of 1942. The latter was certainly familiar to the Italian soldier due to his origins and to his studies of agronomy.

During a break on the field, I wash the laundry invaded by bed bugs. The wash tub and the beetling were part of the equipment.

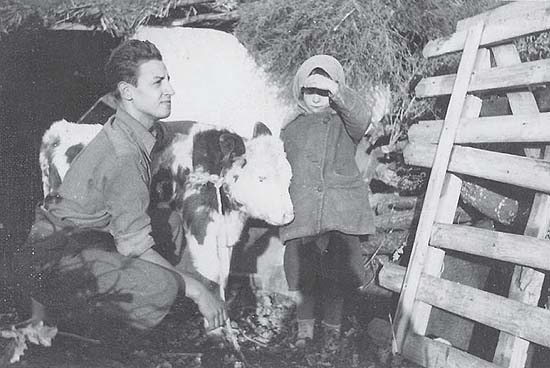

During a break on the field, I wash the laundry invaded by bed bugs. The wash tub and the beetling were part of the equipment. Bruno Damiani, a soldier I met in Russia, with whom I shared so many moments of that forced inactivity. He is beating the ears of corn after the harvest together with a fellow soldier. The few wheat collected and ground was used to bake primitive loafs of bread.

Bruno Damiani, a soldier I met in Russia, with whom I shared so many moments of that forced inactivity. He is beating the ears of corn after the harvest together with a fellow soldier. The few wheat collected and ground was used to bake primitive loafs of bread. Peasants collecting the leftover food for themselves. The boy to the right holds a mess-tin in his hand.

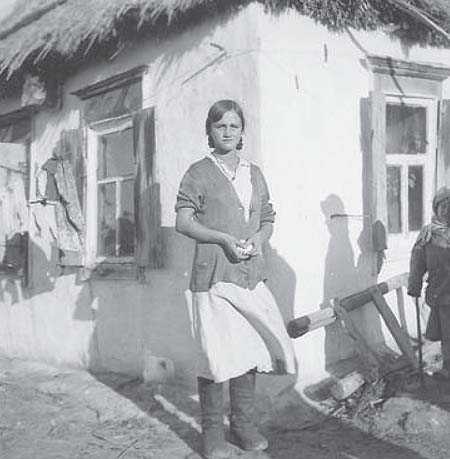

Peasants collecting the leftover food for themselves. The boy to the right holds a mess-tin in his hand. Kantemirovka. A peasant girl in front of an izba in the village where my division survived the winter months.

Kantemirovka. A peasant girl in front of an izba in the village where my division survived the winter months. Bruno Damiani and I distributing the field post. The soldier to the left calls the names: a tense expectation is seen on the faces. At the time we slept in the truck between the boxes of linen, rugs, shoes and uniforms. We were also responsible for ordering the things the division was in need. In summer we stationed in a marshy region near the village of Stalino, and we asked for bednets, which of course did not come. In early October, when it was getting cold, we ordered warm clothes such as undercoats of plush and boots of a bigger size to fit the woolen socks. One day, already in Kantemirovka, we were assigned to unload a wagon at the railway station. However, the shipment was not the longed-for warm clothes, but the bednets we had ordered in the summer.

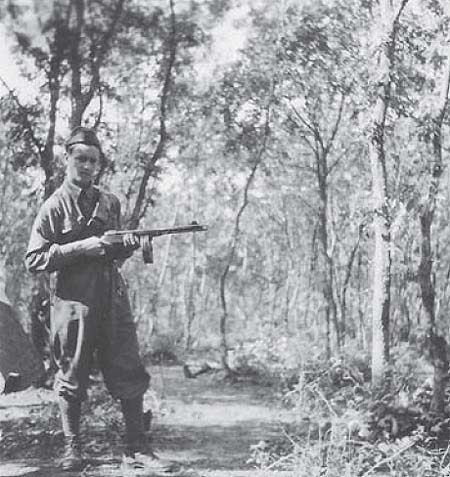

Bruno Damiani and I distributing the field post. The soldier to the left calls the names: a tense expectation is seen on the faces. At the time we slept in the truck between the boxes of linen, rugs, shoes and uniforms. We were also responsible for ordering the things the division was in need. In summer we stationed in a marshy region near the village of Stalino, and we asked for bednets, which of course did not come. In early October, when it was getting cold, we ordered warm clothes such as undercoats of plush and boots of a bigger size to fit the woolen socks. One day, already in Kantemirovka, we were assigned to unload a wagon at the railway station. However, the shipment was not the longed-for warm clothes, but the bednets we had ordered in the summer. I’m trying the Parabellum, a light machine gun seized from the Russian prisoners. It could fire 75 shots, while our First World War model 91 had a magazine of only 6 shots.

I’m trying the Parabellum, a light machine gun seized from the Russian prisoners. It could fire 75 shots, while our First World War model 91 had a magazine of only 6 shots. Me, playing the accordion on a sunny fall afternoon. It was a recreation for the soldiers, but also for the Russian civilians who invited me to play Italian songs at their feasts of baptism and confirmation. There, on the Russian tables I often found the white bread shipped for the soldiers as well as the cognac intended to warm us.

Me, playing the accordion on a sunny fall afternoon. It was a recreation for the soldiers, but also for the Russian civilians who invited me to play Italian songs at their feasts of baptism and confirmation. There, on the Russian tables I often found the white bread shipped for the soldiers as well as the cognac intended to warm us.There is an entirely Italian mythology resumed by the motto “Italiani, brava gente” (Italians are good people), intended to sweeten the wartime behavior of the Italian fascists and soldiers, which benefited a lot from the great shadow cast by the ruthless behavior of the Nazis and the Wehrmacht. In spite of this myth, history has shown that the Italian army also committed war crimes in Libya, Ethiopia, Greece, Albania and Yugoslavia. To my knowledge there are twelve Italians charged of war crimes committed in Russia who have never been handed over to the Soviet authorities. However, there were many other people who paid for both themselves and the sins of others.

We paid dearly for the crimes of fascism, for the crimes of the Italian people in Albania, in Africa, in Russia. Yes, that’s just what I mean: the crimes of the Italian people. Because to a lesser or a greater extent every Italian was a fascist. Between two rallies everybody believed in the imperial future and in the holy war. Even those few who clearly understood and knew what was going on, if were not in prison, are guilty: guilty of silence. And the army paid for all, by fighting. Forget the bunch of officers, the aspiring assholes, the careerists, the criminals. I’m speaking about the “little army”, the real one, the one made up of poor people. My army, the one I knew. [...] We fought for a mistaken war, and we knew this. Our soldiers died miserably. The wounds were bandaged up with toilet paper. We were left without weapons, without supplies. Such was our war. In the early days the fanatics, the pure ones died smiling. But later the pure ones also started to curse. Did we fight for fascism, for Italy, for the army, for ourselves? We fought as humans, and that’s all.

Nuto Revelli, La guerra dei poveri (The war of the poor), Einaudi, 1993 (first edition 1962)

Among the Italians who managed to survive on the Russian front and the tragic retreat of 1943, there were countless witnesses of the generosity and the warm care they received from the Russians.

Manfrini survived due to a combination of special circumstances which is worth to tell. His mother had a dream that she considered an omen, in which she saw him dead. She implored the army chaplain to forward a letter to her son in which she informed him about her imminent operation and that she would refuse to submit herself to it if he would not come home. The details and the further thread of the story become uncertain at this point. Only the final result is known with certainty: Manfrini received a letter giving him, by mistake, the false news of his mother’s death. Subsequently he received permission to leave for Italy.

The square in front of the railway station in Kiev. I arrived in Udine at the end of November, having turned twenty on November 21, during the journey.

The square in front of the railway station in Kiev. I arrived in Udine at the end of November, having turned twenty on November 21, during the journey.

16 comentarios:

Qui l’immagine di una Sertum militare (la Sertum, casa italiana, produsse motociclette dal 1932 al 1952):

http://www.motoinfo.it/public/images/motodepoca/sertum_rid.jpg

Sono stati tanti i soldati italiani mandati in guerra ad affrontare l’inverno russo con le suole degli scarponi fatte di cartone, con la biancheria che veniva bollita nelle stesse marmitte in cui si preparava il rancio, per tentare di eliminarne i pidocchi che però continuavano poi a uscire dai polsini e dai colletti. Il freddo, la fame, gli stenti, l’assurdità della guerra: tutte queste cose non ci sono, nelle pur belle foto del post, che mostrano una faccia quasi umana del conflitto, se mai ce ne può essere una (è detto bene: il mito degli Italiani brava gente).

C’è un una strada, in alto sui crinali delle Langhe, su cui passava all’epoca una corriera; i contadini chiamati alle armi raggiungevano con ore di cammino quella strada, e prendevano la corriera iniziando un viaggio che li avrebbe portati fino in Russia.

Quasi nessuno di loro ha più fatto ritorno.

Grazie, Effe! Ho tradotto questo commento anche per la versione ungherese. Sí, infatti, queste immagini sono troppo idilliche se si pensa com’era la guerra e com’è finita. Ma penso che questa bellezza rifletta più l’innocenza del ragazzo che le ha scattate e la bellezza che lui era capace di vedere anche in quella miseria umana.

A change of comments between an old reader, blist, and me in the Hungarian version of Río Wang:

blist:

“I do not know whether the memories of the old man are imprecise or the translation, but on picture 15 we do not see a Parabellum.

By Parabellum we usually understood the 9x19 munition as well as the weapons using it, chiefly the Luger (P08 or P38) guns, while the young Italian soldier has a Soviet PPS-41 machine gun in the hand, which used a 7,62x25 (so-called TT) munition.

However, it is also true that a part of the seized weapons were transformed for the use of the Wehrmacht by the change of the barrel to use 9x19 munition.

And for the preparation to war [para bellum] it is all the same…”

Studiolum:

“Thank you for the precisation. Francesca in the original Italian post adopted without change the captions of the Italian album published in 2010, where they also wrote Parabellum. It was perhaps Manfrini who did not remember well or, what is more probable, he did not use the Soviet weapon too much (given that he did not spend a long time on the front anyway), and this – mistaken – name put roots in his memory.”

Perdona la pedanteria e probabilmente la ridondanza, Effe, ma queste cose non ci sono perché le foto sono una selezione (mia, soggettiva) di una selezione (le foto pubblicate) di una selezione (le foto consegnate all'editore) di una selezione (i fotogrammi effettivamente estratti dal fluire del film della realtà vista) di una selezione (la realtà vista) di una selezione (la realtà) di una selezione (qualche mese di permanenza in Russia, prima del dicembre del 1942 e apparentemente mai in prima linea).

La prima selezione, l'unica su cui sono potuta intervenire, l'ho operata con difficoltà, perché avrei voluto copiarle tutte (c'è anche la sua Sertum) e - per le tue stesse perplessità - proprio perché mancava la guerra. Anche le ultime foto, prese all'inizio dell'inverno, di cui qui non c'è traccia, mi avevano lasciato più di qualche dubbio: una didascalia, ad esempio, riporta una temperatura di -31°C e nella foto corrispondente il soldato posa ancora una volta solitario, ancora durante la guardia al nulla, in cappotto e con berretto di pelo di coniglio (in un'altra con un normale berretto di lana) in assenza di visibili sofferenze o fatiche. Alla fine mi sono convinta, nonostante i miei dubbi, a pubblicarle così, anche (e forse proprio) perché contrarie alle nostre comuni aspettative. Aggiungo che in certi casi è la didascalia ad avere attirato la mia attenzione. Pensa al suo incontro con i ragazzini del ghetto di Leopoli. Li ha visti, ne ha viste le condizioni di reietti, ne ha visto la fame e la povertà: dopo la multipla selezione detta, ma prima che facessi la mia, non se ne trova traccia se non nel microracconto della didascalia sotto i camion Fiat. Io ne ho dedotto il carattere di quel particolare soldato, il suo senso di umanità, forse di pudore, più che il senso di una testimonianza storica completa. È Manfrini che vediamo o, meglio, sono i suoi desideri dei suoi vent'anni che vediamo, nient'altro. Come in ogni foto, del resto. Ed è grazie a te che ho potuto ragionarci un po' di più stasera, sperando di essere riuscita in qualche modo anche ad esprimerlo.

Grazie per la traduzione, Studiolum. Sì, nell'originale dice Parabellum.

Francesca, condivido il tuo ragionamento; d’altro canto, anche io nel “leggere” le foto ho operato in modo più o meno consapevole una selezione, trattenendo solo quello che un po’ mi ha urtato. E quello che mi ha urtato è l’ottica estetizzante della guerra, la sua versione da cartolina, da propaganda e, come dire, a prova di censura (mi riferisco evidentemente, al fotografo, non a te).

Queste fotografie sono utili a testimoniare, per l’appunto, una visione distorta, edulcorata e presumo inculcata della guerra, che invece non ha mai nessuna bellezza. Nemmeno in un pur bel libro come L’Armata a cavallo (che queste foto di retrovie mi hanno richiamato alla mente), la guerra è qualcosa che si possa ritrarre in una bella foto da inviare a casa con saluti e baci.

Interessante la tua osservazione sui ragazzini di Lvov, che in effetti restano solo nelle parole (e vengono annotati, mi pare, anche con un certo distacco, come nella nota di un entomologo); nella foto, invece c’è solo un insieme freddo e ordinato (forse l’ordine ha una funzione rassicurante e apotropaica, in mezzo al caos della guerra) di mezzi meccanici, un insieme da cui la vita, e la morte, sono prudentemente escluse.

In definitiva: personalmente non vedo sogni, in queste foto, ma solo cecità, come se il fotografo si fosse dimenticato, prima di scattarle, di rimuovere il copriobbiettivo della propria coscienza.

Grazie, in ogni caso, per l’opportunità di questo confronto.

Per giustamente giudicare queste foto si deve rendere conto anche del ruolo sociale della fotografia nell’epoca, e anche dei modelli che un dilettante fotografo ventenne, nato nell’anno della Marcia su Roma, poteva conoscere ed imitare. Pur non conoscendo di fondo il materiale fotografico pubblicato nelle riviste dell’Italia dell’epoca, credo che la loro maggioranza rappresentava in maniera più o meno edulcorata i momenti festivi – o comunque “degni” di rappresentare – della vita, ed era a questi momenti che la fotografia come pratica sociale era riservata. Non credo che la fotografia sociografica, la rappresentazione della vita dura, brutta e sincera – quella tanto apprezzata nel cinema neorealista – abbia avuto grande influenza nei tempi di Mussolini, quando pure nell’Ungheria, che nell’epoca con Kertész, Capa, Brassaï, Moholy-Nagy ed altri era all’avanguardia della fotografia, si era appena infiltrata. Se presso le famiglie di contadini ungheresi fra le migliaie di foto sopravvissute che io ho visto lavorando presso un museo di provincia non c’era nessuna che rappresentava il lato brutto della vita, allora non c’è da meravigliare se anche il ragazzo italiano ha naturalmente selezionato i momenti “belli” per registrare, non considerando quelli “brutti” o “comuni” degni da fotografare.

Per quanto alle didascalie e alla loro relazione con il soggetto delle foto, si deve essere molto attenti. Benché scritte nella prima persona, io dubito che siano veramente formulate da una persona quasi novantenne al momento della composizione e pubblicazione del libro. Ritengo più verosimile che siano i figli che hanno descritto (o raccontato) all’editore del volumetto ciò che il padre gli aveva raccontato a proposito di ciascun luogo rappresentato nelle foto. E’ naturale che il risultato di una simile catena di trasmissione abbia già poco da dire dei sentimenti del protagonista settant’anni fa.

Due cose ancora. Il primo che sì, Effe, hai ragione in quanto dici sulla cecità del ragazzo. Ma non è appunto Revelli che dice che c’erano ben pochi nell’epoca che sono riusciti di rimuovere il copriobiettivo della propria coscienza? E qui penso anche alla coscienza visuale, severamente sorvegliata nelle società totalitare dell’epoca.

L’altro è solo una curiosità: che per i lettori russi di Río Wang, che sicuramente non devono essere messi al corrente rispetto alla natura della guerra e del nemico, questo post con queste foto presentava qualcosa di inaspettato: vedi per esempio qua (“il nemico con la faccia di uomo”), o qua.

Capisco la questione della cecità. Credo però che se avesse voluto censurare o censurarsi, allora non avrebbe fotografato affatto. Nel suo caso, ho avuto la sensazione che invece lui fotografasse quello che sentiva (forse anche a contrario, come reazione, sì, Effe) e non quello che vedeva. Poi giustamente il discorso si complica per gli influssi dell'estetica del tempo, come ha detto Studiolum, che colpiscono in egual misura la fotografia e la letteratura (aah, Babel).

La questione delle didascalie. Lì vado ancora a sensazioni - come in tutto, del resto - ma lì ancora di più. Ho pensato: le estraevano dalla scatola in famiglia, le fotografie. Il padre le commentava. Ecco, se era un riunirsi periodico e familiare attorno a quel nucleo di memoria, ho pensato che potesse aver sviluppato nel tempo delle parole stabilite, una codificazione a parole del ricordo e quindi che le didascalie fossero il risultato di questo percorso, una cristallizzazione delle parole del protagonista nel tempo. Ma magari mi sbaglio e han fatto veramente tutto i figli e/o l'editore.

Grazie in ogni caso ad entrambi per gli interventi e la pazienza.

Francesca e Studiolum,

questo scambio mi è stato utile per focalizzare meglio quella che considero una nota stonata. A stridere non è solo il racconto della guerra che fa a se stesso quel ragazzo di vent’anni nel 1942 (e che pochi, a quell’epoca, avessero aperto gli occhi, non lo credo; dopo meno di un anno, con l’otto settembre 1943, sarebbe iniziata – evidentemente non nascendo dal nulla - l’esperienza della Resistenza; e chissà cosa ne ha raccontato, quello stesso ragazzo). La nota stonata è il progetto editoriale che, oggi, ci propone quella stessa visione, estetizzante e falsa, della guerra italiana in Russia. Il libro può essere un documento storiografico interessante proprio per quello che non c’è, per quello che manca, che è taciuto, ignorato, dimenticato. E’ una valenza per negazione, si potrebbe dire, o in absentia. Vale, ma solo per la distanza che lo separa dalla verità.

Per muoversi lungo quella distanza, lascio l’indicazione di altre fotografie - un paio delle quali sembrano ricondurre proprio all’Armata a cavallo, tanto per chiudere il cerchio - che meglio ricordano (lo sappiamo tutti, in realtà) cos’è stata la campagna di Russia dell’esercito italiano nel ’41-’43: assideramento, fame, fatica, sconfitta.

1

2

3

4

5

Alcune annotazioni a corredo delle foto precedenti:

I soldati dell'ARMIR (Armata Italiana in Russia) sono armati ancora con il vecchio fucile 1891, i fucili mitragliatori e le mitragliatrici più moderne soffriranno le rigidissime temperature invernali inceppandosi, i trenta carri armati L6/40 hanno corazze che non resistono ai fucili anticarro sovietici, le batterie anticarro con i pezzi da 47 sono inadatti a fermare i T-34 russi. Anche la logistica è carente: radio e automezzi sono scarsi, derrate e vestiario sono insufficienti (ogni reparto si arrangia come può a danno delle già scarse risorse della popolazione contadina locale). I soldati riescono a sopravvivere soltanto grazie a indumenti civili portati da casa, le scarpe però sono sempre le stesse della campagna di Grecia (valide per tutti gli scenari bellici, dal Sahara alla Russia), marciscono ben presto e diventano responsabili, insieme alle fasce che stringono i polpacci, dei tanti congelamenti agli arti inferiori. Nelle retrovie imperversano lo sciacallaggio e la borsa nera sui pacchi viveri e vestiario provenienti dalle famiglie

E poi, alla fine:

Ormai quella della colonna in ritirata è diventata una corsa affannosa, cui moltissimi non riescono a partecipare, si sdraiano, si siedono sfiniti sui bordi delle piste, a centinaia, implorano aiuto, ma la colonna non può fermarsi, i più deboli sono abbandonati a un tragico destino di morte. I validi proseguono, con disperazione, sono ormai senza viveri, ne fanno le spese i muli che uno dopo l'altro vengono abbattuti, rapidamente fatti a pezzi e mangiati. Sono scene allucinanti tra i gemiti, le urla dei feriti, di quelli colpiti da cancrena, i quali ormai sanno che saranno abbandonati

Sì. Queste foto sì che riflettono molto più fedelmente la realtà. La stessa realtà che anch’io conosco di quelle foto che rappresentano nelle stesse condizioni l’armata ungherese in ritirata dallo stesso Don, fra cui duecentomila non sono ritornati. Ma per me le foto del ragazzo non escludono questa realtà finché il lettore (o l’editore) non la vuole escludere.

I thought that "beating the ears of the wheat" is called "threshing". Sometimes they used animals. Remember there is also the most beautiful Biblical command:

Thou shalt not muzzle the ox when he treadeth out the corn.

(Sometimes he was muzzled to prevent him from eating while working.)

Yes, perhaps you are right and I made a too literal translation from the original Italian caption’s “battere il grano”. But the Italian also has the verb “trebbiare”, and it might be meaningful that this miserable operation, beating the grain out of what remained in the field after the harvest, is indicated with “beating” and not with “threshing”.

'Trebbiare' sound like what is known in English as 'gleaning'. For example there is the famous 1857 painting by Millet called 'The Gleaners'.

Yes, I think it is the right word. The difference between “threshing” and “gleaming” is moreor less the same like between “csépel” and “tallóz” in Hungarian.

Publicar un comentario