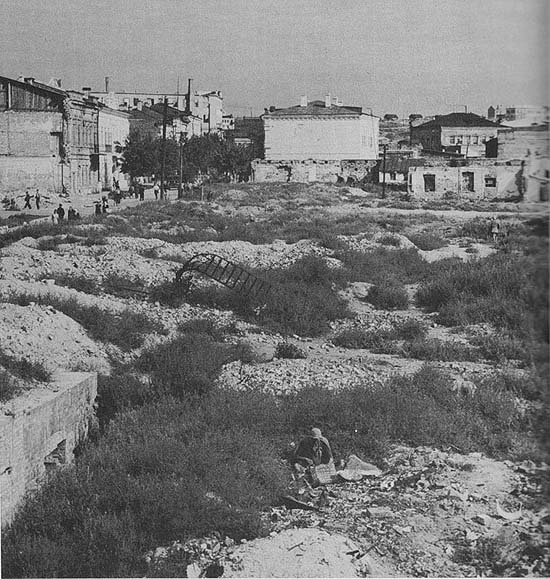

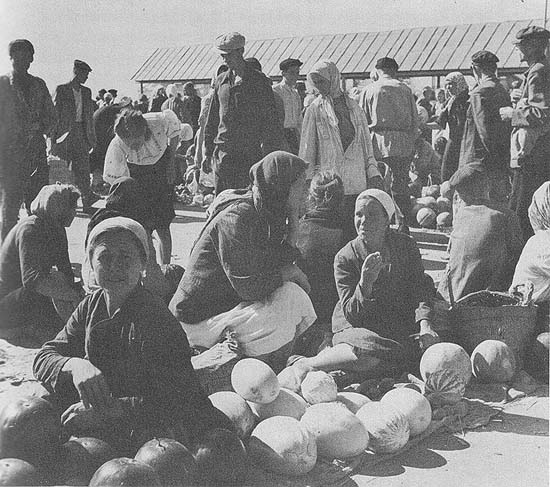

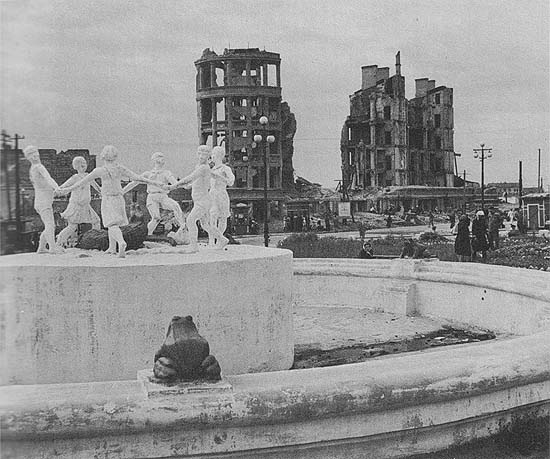

“Our windows looked out on acres of rubble, broken brick and concrete and pulverized plaster. We grew more and more fascinated with this expanse of ruin, for it was not deserted. Underneath the rubble were cellars and holes, and in these holes many people lived. We would watch out of the windows of our room, and from behind a slightly larger pile of rubble would suddenly appear a girl, going to work in the morning, putting the last little touches to her hair with a comb. She would be dressed neatly, in clean clothes, and she would swing out through the weeds on her way to work. How they could do it we have no idea. How they could live underground and still keep clean, and proud, and feminine. Housewives came out of other holes and went away to market, their heads covered with white headcloths, and market baskets on their arms. It was a strange and heroic travesty on modern living.”

“In the afternoon we walked across the square to a little park near the river, and there under a large obelisk of stone, was a garden of red flowers, and under the flowers were buried a great number of the defenders of Stalingrad. Few people were in the park, but one woman sat on a bench, and a little boy about five or six stood against the fence, looking in at the flowers. He stood so long that we asked Chmarsky to speak to him.

Chmarsky asked him in Russian, “What are you doing here?”

And the little boy, without sentimentality, in a matter-of-fact voice said, “I am visiting my father. I come to see him every night.”

Chmarsky asked him in Russian, “What are you doing here?”

And the little boy, without sentimentality, in a matter-of-fact voice said, “I am visiting my father. I come to see him every night.”

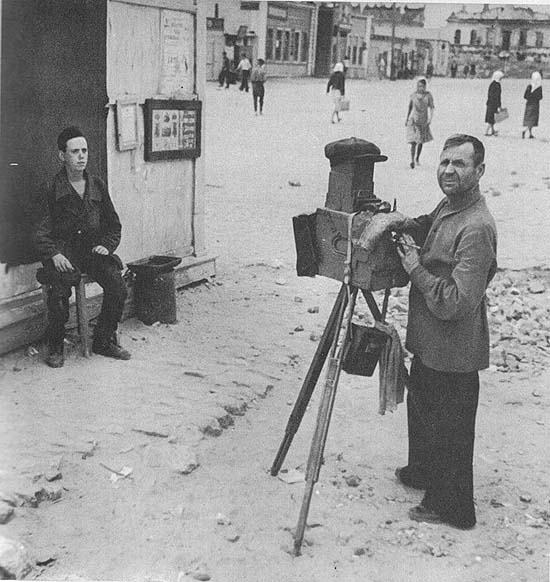

“In one market at Stalingrad there was a photographer with an old bellows camera. He was taking a picture of a stern young army recruit, who sat stiffly on a box. The photographer looked around and saw Capa photographing him and the soldier. He gave Capa a fine professional smile and waved his hat. The young soldier did not move. He gazed fixedly ahead.”

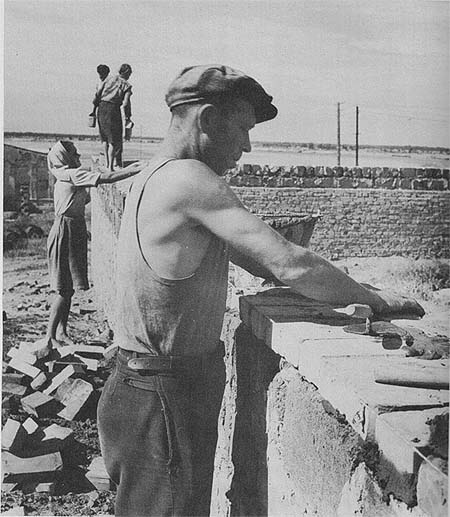

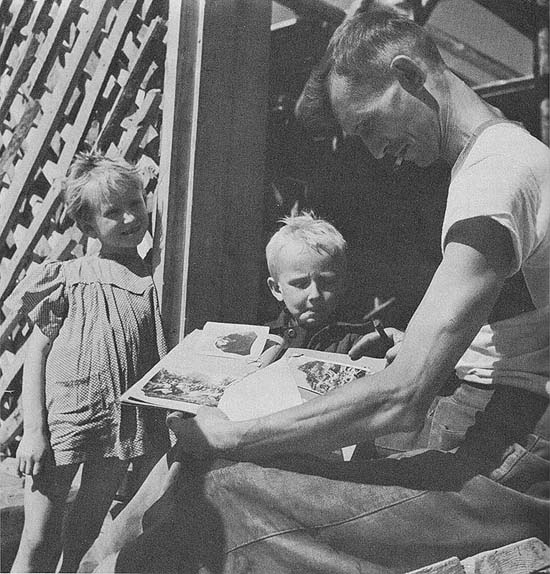

“We stopped at a tiny house that a bookkeeper in a factory was building. He was putting up the timbers himself, and he was mixing his own mud for plaster, and his two children played in the garden near him. He was very agreeable. He went on building his house while we photographed him. And then he went and got his scrapbook to show that he had not always been ragged that he had once had an apartment in Stalingrad. And his scrapbook was like all the scrapbooks in the world. The photographs showed him as a baby, and as a young man, and there were pictures of him in his first uniform when he entered the Army, and pictures of him when he came back from the Army. There were pictures of his marriage, of his wife in a long white wedding gown. And then there were pictures of his vacations at the Black Sea, of himself and his wife swimming, and of his children as they were growing. And there were picture postcards that had been sent to him. It was the whole history of his life, and all the good things that had happened to him. He had lost everything else in the war.

We asked, “How does it happen that you saved your scrapbook?”

He closed the cover, and his hand caressed this record of his whole life, and he said, “We took very good care of this. This is very precious.”

We asked, “How does it happen that you saved your scrapbook?”

He closed the cover, and his hand caressed this record of his whole life, and he said, “We took very good care of this. This is very precious.”

2 comentarios:

Thanks a lot for this post. I've read the Russian Journal, but the photos included int he book were not of great quality. I can finally see them properly.

Yes, also the editions I have read (both the English original and the Hungarian translation) had very low quality illustrations. Fortunately I have found them all on a Russian site, scanned either from a better edition or from a Capa album.

Publicar un comentario